Tekst av Morten Aashammer Gjennestad

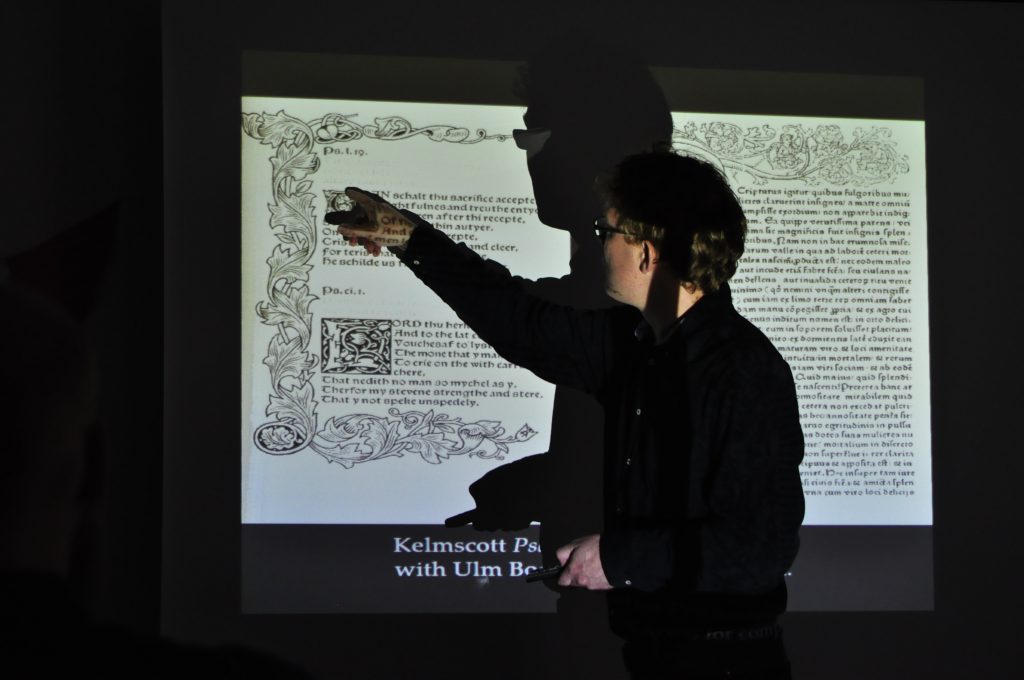

On the last day of the Ugress 2016 festival Yuri Cowan, professor of English literature at the department of language and literature at NTNU, held a talk entitled “The Small Press Movement, Book Design, and the Origins of Modernism” at Lademoen Kunstnerverksted. The smell of ink that still lingered in the room from the graphic workshop hosted earlier in the day helped set the mood.

Cowan spoke of the Small Press Movement, sometimes referred to as the Private Press Movement, which was a reaction to the increasing industrialization of the printing industry in the late 1800s. The small printing workshops of earlier centuries, with an emphasis on craftsmanship, had been replaced by the larger and more efficient industrial presses. Books could now be produced at a much lower cost and were no longer the exclusive domain of the wealthy, but for the aesthetically-minded this came at a cost. Gone were the beautiful and ornate books produced by earlier book makers.

William Morris

The polymath William Morris, also an early practitioner in the fantasy genre and proponent of socialism, was a central figure in the larger Arts and Crafts Movement which, in addition to books, included furniture, cutlery, stained glass windows and many other of the decorative arts. His artistic philosophy is perhaps best summarized by his statement that one should: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful.”.

Morris was influenced by medieval artists, which is evident in much of his work, but especially in his book designs. At Kelmscott Press Morris collaborated with like-minded individuals to print books of an exquisite quality, the best known of which is perhaps «The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer». Morris designed his own types and drew decorations for the pages. The press availed itself of modern technology, but always for the purpose of creating books that rivaled those of earlier masters. The goal was to create books that combined the individual material components of the book, such as the cover, binding, and illustrations, and created an integration of text and ornament.

Do-it-yourself

The Arts and Crafts movement would in turn act as an inspiration for Art Nouveau and eventually Art Deco and later authors, such as Leonard and Virginia Woolf, would also print their own books via presses modelled on Kelmscott Press and its contemporaries. They too saw the value in an author’s ability to exert control on the material aspect of their books. Many of these newer presses, such as The Folio Society, are still with us today.

Cowan pointed out how this do-it-yourself-attitude of the Small Press Movement persisted in the forms of chapbooks and eventually zines. In our own highly digitized society and thanks to modern word processing software that allows us to tinker with fonts and alignment, we might now feel as though the process of physically manifesting our texts has finally been democratized. Cowan, however, warns that we are still constrained by the limitations of the software we use. True self-expression is therefore still best achieved with the aid of a self-made typeface, an exacto knife, and a photocopier.